The Munsons of Texas — an American Saga

Chapter Nine

HENRY WILLIAM MUNSON AND ANN BINUM PEARCE AND THEIR MOVE TO TEXAS — 1817-1828

SUMMARY

After Henry William Munson and Ann Binum Pearce were married in 1817, they lived in Louisiana for about seven years. There they had four sons, the first three of whom died before reaching the age of two. In 1824 the family moved to the Trinity River in the Atascosita District of Mexico (now Liberty County, Texas). Mordello Stephen Munson was born there in 1825. The family lived there for about four years before moving on to the Austin Colony in what is now Brazoria County, Texas, in 1828.

Henry William Munson and Ann Binum Pearce were married on May 12, 1817, presumably at the Pearce plantation near the present town of Cheneyville, Rapides Parish, Louisiana. Henry William was 24 years old and Ann was barely 17. Her father had died three years earlier and she had probably been living with her step-mother, Elizabeth Chafin Pearce, and her baby half-sister, Tuzette.

Little is known of Henry William and Ann's first seven years of

marriage. It is known that they were living in Rapides Parish in

1820, and it is assumed that they lived there from the time of

their marriage until their move to Texas in 1824. One wonders if

they lived at Lunenburg, the Pearce Plantation; at nearby "Oakland

Plantation", a few miles up the Red River; or elsewhere. It is

known that they had four sons during these seven years, and herein

lies one of the saddest stories of Munson history. On October 22,

1818, son Samuel was born and on August 2, 1819, baby Samuel died.

On September 12, 1820, son Henry W. ![]() was born and in November of

1821, baby Henry died. In 1822 son Robert was born and in 1823 baby

Robert died. On February 24, 1824, son William Benjamin was born,

and he, their fourth son, lived and grew to maturity.

was born and in November of

1821, baby Henry died. In 1822 son Robert was born and in 1823 baby

Robert died. On February 24, 1824, son William Benjamin was born,

and he, their fourth son, lived and grew to maturity.

The naming of these sons is interesting and may provide a clue to Henry William's recent ancestors. The second was named Henry W. for his father, the third was named Robert for Henry William's admired uncle, and the fourth was named William Benjamin, probably for Ann's father, William Pearce. No son was ever named Jesse, but the first was named Samuel. Could this have been for a brother and/or the father of Jesse and Robert — the early Samuel Munson Sr., who was in Fayette County, Kentucky, in 1790 and apparently in Mississippi and Louisiana (together with a Samuel Elder Munson) in 1810-1817? (See Inset 11).

The 1820 U. S. census for Rapides Parish ![]() lists Henry Munson with a household of one male, 16-26 years old,

and one female, 16-26. Their first child, Samuel, had died in 1819,

and the second child, Henry, was born in November of 1820, after

the date of the census.

lists Henry Munson with a household of one male, 16-26 years old,

and one female, 16-26. Their first child, Samuel, had died in 1819,

and the second child, Henry, was born in November of 1820, after

the date of the census.

Between February and September of 1824, Henry William and Ann moved to the Atascosita District, State of Coahuila y Tejas, in the newly independent Republic of Mexico. With them on this move were baby William Benjamin, just a few months old; Henry William's brother, Micajah, and half-brother, Jesse P.; Micajah's wife, Elizabeth Everett, and their two daughters; and possibly William Everett, Elizabeth's brother. Thus all of the descendants of Jesse Munson and their families moved to Texas.

It is interesting to remember here that the 1829 records of the Court of Equity in Barnwell County, South Carolina, in a proceeding on the estate of Wright Munson, state: ". . .and when Overstreet heard [Wright] Munson was dead he had himself appointed [administrator]. The Munson heirs never have appeared or sent for their money, and defendant does not know who they are or where they are but understands they live in Texas" [see Chapter 4]. This suggests that Wright could have been their father — or a childless brother.

A compelling reason for their move was surely free Mexican land — one league — 4,428 acres for each family — under the new Mexican land-grant policy. Another reason may have been the bad experiences with the deaths of Henry and Ann's first three sons in Louisiana, while continuing economic hardships were usually a contributing reason for such moves.

The approximate date of their move to Texas comes from an 1824 letter, the oldest document in the Munson family collection, written by Delia Pearce Dunwoody, Ann Munson's sister, from Rapides Parish, Louisiana, to Mrs. Nancy B. Munson. Ann was called Nancy by her family and even signed some legal documents with this name. The letter reads:

Bayou Beouff, february 28th — 1825

Dear Sister

It is with great pleasure that I have the pleasing sight to behold your Dear companion [Henry William] once more and likewise feel thankfull to hear the welcome news that you and your Dear little son are yet alive and blesst with a reasonable share of health. I felt uneasy about you for we have not heard any strait accounts from any of you since you left red river [Rapides Parish]. I feel sorry that my letter which was rote in september [1824] did not go to you. Mr. Garner promist me faithfully that he would send it to you. We all wondered among ourselves what was the reason you did not rite tho perhaps if you had of rote the letter might get miscaried - - - I had the fever a few days past but thank the lord I have got able to go about again . . .Mr. Dunwoody has had a few atacks of the third day chill and fever but he do not lay up much for it. . .Kiss my Dear litle William for me. . .I remain your ever affectionate loving Sister til death.

Delia Dunwoody

The reference to "your dear companion"

is surely to Henry William, who appears to have made a trip to

Rapides Parish and visited the Dunwoodys and probably carried this

letter back to his wife. Since son William Benjamin was born in

Louisiana on February 24, 1824, and Delia Dunwoody refers to her

letter of September, 1824, one can place the time of the move

between these dates.

Mexican Independence and New Land-Grant Policies [1]

The events that led to the Munsons' move to Texas were woven from the successful Mexican struggle for independence from Spain and the resulting liberal Mexican land settlement policies, as opposed to Spain's policy of expulsion and forbidding of American settlers.

By the early 1800s relations between the inhabitants of Mexico and their rulers from Spain had reached a sad state. In Spain the government was in shambles from years of war and defeat by the armies of Napoleon. In Mexico care was taken that native-born citizens, no matter how capable nor how noble, would not hold any important office. Corruption in every department — civil, military, and ecclesiastical — was shameful.

Over several decades numerous independent revolutionary groups had sprung up in local areas but were soon defeated by the Royalist armies financed from Madrid. In the summer of 1820, the only organized Mexican revolutionary forces still in the field were in the mountains between Mexico City and Acapulco under Vicente Guerrero and others; plus a small body in the mountains to the east of the capital city — followers of Guadalupe Victoria.

On the Royalist side was a rising young officer, Augustin de Iturbide, a full-blooded Spaniard born in Mexico. In 1820 he was placed at the head of a Royalist force ordered to crush the remaining revolutionary forces. Iturbide, however, being born in Mexico, discerning the deep and growing reactions in favor of Mexican independence, and after being invited by the opposition, resolved to be the one to lead the revolution. It was his desire to divorce Mexico from Spain, to form a new monarchy, and to be the leader with royal dignity and power. To achieve success it was necessary for him to secure the cooperation of the revolutionary leaders and the immensely powerful church dignitaries, and so he did.

On February 24, 1821, having taken a presumed military position at Iguala on the road to Acapulco, he issued the "Plan of Iguala", which declared, among other items, the following principles:

- First, the independence of Mexico.

- Second, the Roman Catholic religion should be supported perpetually Ä "The nation will protect it by wise and just laws, and prohibit the exercise of any other."

- Third, the abolition of all distinction of classes and the union of Spaniards, Creoles, Indians, Africans, and Castilians, with equal civil rights for all (an end to slavery).

This manifesto, first approved by Iturbide's officers, was enthusiastically received by his army, who thereafter marched under the flag of three guarantees: "Independence, Religion, and Equality." Guadalupe Victoria, Vicente Guerrero, and the other old chieftains embraced Iturbide's standard. The whole country was aglow with enthusiasm and from every quarter men were hastening to swell the ranks. Defeat and disaster engulfed the Royalists everywhere and on April 24, 1821, Spain and Mexico signed the Treaty of Cordoba in which Spain accepted the Plan. On September 27, 1821, Iturbide peacefully and in triumph entered the capital of Mexico City and soon established himself in the viceroy's palace.

He immediately formed a ruling junta and called a Cortez of citizens to meet on February 24, 1822. But again, as so often has occurred in history, the successful military leader was not sufficiently skilled in statecraft to successfully carry out his dreams — or maybe the fatal flaw lay in the nature of his dreams: dreams of personal grandeur rather than of good government. In any event divisions quickly developed, followed by acrimonious debate and threats of armed revolt. Many of the older leaders withdrew support and retired to their homes, but on May 18, 1822, mobs in the city beseeched Iturbide to become emperor, and, in a badly divided country, Iturbide was installed as Emperor Augustin I of Mexico on July 21, 1822.

It was during this period of turmoil, on April 29, 1822, that Stephen F. Austin arrived in Mexico City hoping to obtain Mexican approval of his father's Spanish colonization plan for Texas. With capital politics at fever heat, he found it impossible to secure immediate consideration of his claims. To further complicate matters, he found Haden Edwards of Kentucky, Robert Leftwich of Tennessee, Green DeWitt of Missouri, and General James Wilkinson, late of the United States Army, also in the city seeking permission to establish American colonies in Texas. Austin insisted that his claim was prior and peculiar in its merits and should receive consideration aside from the general legislation. With his power fast eroding, Iturbide suddenly dispersed Congress and appointed a junta composed of thirty-five members, and the question of colonization was referred to that body. The junta passed a colonization law and it was approved by Iturbide on January 4, 1823.

This was the first colonization law enacted by Mexico, and it had a profound effect on the future of Texas. It abrogated the royal order of Philip II of Spain prohibiting foreigners in Texas, and decreed that foreigners who professed the Roman Catholic religion should be encouraged to immigrate and would be protected in their lives, liberty, and property. To encourage immigration, the government promised to give out of vacant public lands one labor of land (177 acres) to each farmer and one league (4,428 acres) to each stock-raiser. As an added inducement, immigrants were to be relieved of all tithes, taxes, and duties for six years. Eight years later, the termination of this liberal grant with the imposition of duties was a factor in bringing on the Texas Revolution. There was to be no buying or selling of slaves, and all children born of slaves were to be free at the age of fourteen. These slavery provisions were never enforced in Texas.

The law provided that immigrants might come individually on their own or be introduced by empresarios (agents). For each two hundred families introduced, an empresario was to receive for his own account three haciendas and two labors of land, which equaled fifteen leagues and two labors, or 66,774 acres — but, however great the number of immigrants introduced, any one empresario could not acquire more than 200,322 acres. From this it can be assumed that a major motivation for the rash of empresario applications was the prospect of money to be made from future land sales to new settlers.

On the approval of this law on January 4, 1823, Austin, who had been in the city over nine months, pressed his claim for a special confirmation of the grant given to him and his father by the Spanish authorities in 1821. Jose Manuel de Herrera, Minister of Foreign and Internal Relations under Iturbide, manifested warm friendship for Austin and zealously advocated his claims, and on February 18, 1823, the grant was confirmed. But as Austin was preparing to leave for Texas, a counter-revolution occurred driving Iturbide from power, the colonization law was annulled, and Austin found it necessary to postpone his departure.

During the previous nine months, the opponents of Iturbide had

steadily gained strength outside Mexico City. Generals Vicente

Guerrero, Nicholas Bravo, and Guadalupe Victoria had gathered their

old followers hoping to force a new regime. Antonio Lopez de Santa

Anna, once one of Iturbide's strongest young lions, soon joined

them. Iturbide found himself so abandoned and helpless that on

March 19, 1823, he disbanded the government and formally abdicated

the throne. He was exiled to Italy, but returned to Mexico in

disguise in July of l824. His identity was betrayed by an old

friend, and he was turned over to the custody of none other than

Jose Bernardo Gutierrez de Lara, the author of the butcheries at

San Antonio in 1813, and Augustin Iturbide was executed on July 19,

1824 ![]() .

.

On the downfall of Iturbide, the old Congress reassembled and named an executive council consisting of Generals Guadalupe Victoria, Nicolas Bravo, and Pedro Negrete. A new assembly was elected and on October 4, 1824, they proclaimed a new constitution, afterwards known as the Constitution of 1824.

These were the birth convulsions of the Republic of Mexico.

In March of 1823 Stephen F. Austin felt unwilling to await the

first meeting of the new Congress scheduled for August, so he

immediately pressed the merits of his case upon the newly elected

executive council of Victoria, Bravo, and Negrete, and on April 14,

1823, they reaffirmed the actions previously taken. This final

confirmation gave Austin a land grant containing no limitation as

to territory, nor was a time fixed in which to colonize the first

three hundred families — privileges conferred upon no later

empresario. Austin left for home on April 28, 1823, and

reached the settlement on the Brazos about the middle of July after

an absence of sixteen months. He was welcomed by his colonists who

had already received the joyous news. This perseverance, together

with his following performances, certainly entitles him to the

admiration of every Texan today.

The Munsons Move to Texas

When the news of the triumph of the "Plan of Iguala" and the resulting immigration policies became known in Louisiana, many Americans who had fled before the Spanish raids of recent years began to return to their homes at Nacogdoches, the Brazos, and the Trinity settlements. Then, as the news spread in 1823 of Austin's success and of the liberal land grants available to individuals as well as empresarios, other families decided to move to Texas. These included the families of Henry William and Micajah Munson.

Henry William Munson had passed across the breadth of Texas, from Louisiana to San Antonio de Bexar, in June of 1813. Traversing this virgin countryside in the month of June, a young man with dreams for his future might have observed some very pleasing sights that were not soon forgotten: rich, flower-filled grasslands intermixed with stately trees; flat and rolling landscapes well suited to farming and travel; many rivers and streams; an abundance of wildlife; and a pleasant June climate. On his return to Louisiana after his narrow escape from the Battle of Medina, he may even have crossed the Trinity River at the Atascosita crossing. When the news of the new Mexican land-grant policies spread through Louisiana in 1823, Henry William may have already known the area that he coveted.

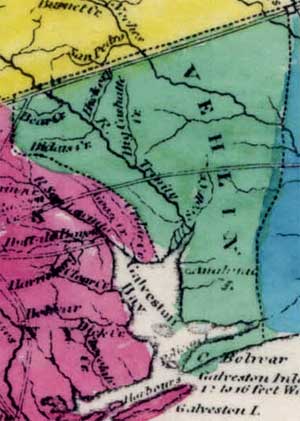

Sometime around mid-1824 the Munsons emigrated from the State of Louisiana, in the United States of America, to the banks of the Trinity River in the Republic of Mexico. The move seems amazingly reminiscent of the emigration thirty-five years earlier of brothers Jesse and Robert Munson from the new state of South Carolina to free land in the Natchez District of New Spain. As stock-raisers with slaves, Henry William and Micajah staked claims to adjacent plots of 4,428 acres each on the west bank of the Trinity River. Their land was just south of the Coushatta Indian village and the river-crossing of the Old Atascosita Road from Louisiana to La Bahia.

The exact location of these plots can easily be identified today. Henry William never received title to his claim and moved his family to Austin's Colony in the future Brazoria County in 1828. Micajah died before 1828 and before titles to the land were finally granted. However, on January 27, 1831, the Mexican Government granted to "Elizabeth Munson, widow of M. Munson, deceased, native of U. S. of the north and residing in this dept. since 6 years. . ." title to one league of land in the Atascosita District, described as "adjoining and below the league of land surveyed for Henry W. Munson" [2]. Today this league is shown as the "Elizabeth Munson Survey" on the original land grant map of Liberty County published by the Texas General Land Office. All abstracts of title in this survey trace their ownership back to this grant. If the Henry W. Munson league was adjacent and to the north, it is shown on this General Land Office map as the "Town of Liberty, South League", and would today include much of the towns of Liberty and Dayton, Texas.

These claims were the locations of the first homes of the Munsons in Texas. In the approximate center of the Elizabeth Munson Survey, among scattered oaks and underbrush, there stands today a monument set during the Liberty Bicentennial Celebration in 1956 marking the location of the first homestead of Elizabeth and Micajah Munson [3].

These new homes of the Munsons were immediately less than satisfactory. A letter dated January 29, 1825, from J. Iiams to Stephen F. Austin reads as follows:

Sanja Cinto January 29th 1825

Dear Sir:

Messrs Henry and Micajah Munson living at present on this side trinity and being somewhat disappointed in their Settlement by the overflow that river desire of me to enquire of you whether they can be admitted into your Colony and obtain the title of Land.

If they can be admitted they wish to have Lands near meon Cedar buyo. . .and they will commence settlement Immediately they are men of respectability having each a family and about 17 Slaves each with good stock of Cattle etc. etc. They also wish to enquire whether more Land can be granted in proportion to the number of Slaves. . .please write me a line on the above Subject and if they will be accepted direct the survey as they are desireous to have it accomplished. . . J. Iiams

No move was made as a result of this inquiry.

Ann Binum Munson was pregnant again. On April 25, 1825, she gave birth to her fifth son in a period of five and one-half years. She was 25 years old. Early records suggest that this son may have been named Stephen Mordella Munson, probably to be known as Stephen. This is not surprising, because Stephen had been a common name in the Pearce family for many generations, and Mordella was the name of the Spanish officer who had saved Henry William Munson at the Battle of Medina. The 1826 census of the Atascosita District, signed by his father, lists him as Stephen B. Munson. The middle initial is surely a careless error, noting that his brother's name, immediately preceding, was William B. Munson. In his early years, his name was interchangeably written as Mordella or Mordello. For instance, his name on the roll at Rutersville College in 1842 was Mordella S. Munson, and many early Brazoria County legal documents show his name as Mordella. Throughout his adult life he was known as Mordello Stephen, although it was frequently written as Mordella.

Family tradition tells that Mordello Stephen Munson was the first white child born at the old Coushatta Indian village on the Trinity River. Here, in 1825, began the seventy-eight-year lifespan of this illustrious member of the Munsons of Texas. His impact was such that at least six separate contemporary families named sons Mordello or daughters Mordella for him, and in 1980 a grandson of one of his great-grandsons was named Luke Mordello Munson, and, in 1984, a grandson of another of his great-grandsons was named Ryan Stephen Gray.

Events of the following few years show Henry William Munson to have been one of the leaders of the Trinity community. A continuing problem was that while Mexican authorities were granting land titles to settlers in Austin's Colony, no action was forthcoming to grant titles to homesteads in Atascosita. The distance from San Antonio and from the new capital of Saltillo was far, the district had no established government nor single leader, and the Mexican administration moved slowly in such matters. This continued to plague the residents and finally contributed to Henry William Munson's decision to leave the area for Austin's Colony on the Brazos.

The year 1826 was a time of severe land and settlement frictions throughout East Texas, which led to the Fredonian Rebellion of January, 1827. During this year, possibly prompted by these threatening events, the citizens of Atascosita organized their district under the Mexican colonization laws. They elected neighbors George Orr and Henry William Munson (both survivors of the Battle of Medina) as joint Alcaldes (chief municipal officers), took a census, set their boundaries, and held an election to determine the preference of the population on joining the Austin Colony or the Nacogdoches District. During this period, Henry William Munson served as an examining judge for the district and was at times referred to in documents as Judge Munson. It is obvious that he had a good education, and his involvement and leadership leads one to believe that he might have had some legal training between 1813 and 1817.

The now famous Atascosita Census of 1826, dated July 31, lists

331 names of white men, wives, and children and is signed by

Matthew G. White, Joseph W. Brown, George Orr, and Henry W. Munson

[4]. The total population was 407 as

the names of the 76 slaves were not listed. The census is of great

historical value in establishing the names, numbers, and ages of

residents, their occupations and the states of their birth, and the

number of slaves. This is the source of the important Munson family

information that Micajah Munson was born in South Carolina between

approximately August l, 1788, and July 31, 1789. The data listed on

the Munsons are as follows:

| Name | Age | Slaves | Where born | Occupation | |

| over 14 | under 14 | ||||

| Munson, Micajah B. | 37 | 8 | 5 | S. Carolina | Saddler, Farmer & Stockraiser |

| Everett, Elizabeth | 32 | N. Carolina | Wife of Micajah B. Munson | ||

| Munson, Ann Eliza | 6 | Louisiana | Daughter | ||

| Munson, Martha | 3 | Ditto | Ditto | ||

| Munson, Henry W. | 33 | 9 | 6 | Mississippi | Farmer & Stockraiser |

| Pearce, Ann B. | 26 | Georgia | Wife of Henry W. Munson | ||

| Munson, William B. | 2 | Louisiana | Son | ||

| Munson, Stephen B. | 1 | Texas | Ditto | ||

Henry W. Munson owned the largest number of slaves in the district, and Micajah owned the second largest number. The census presents many interesting facts concerning the people and the times. Of the 104 heads of families listed, only six were born outside the United States, and these were from Ireland, England, Italy, and only one from Mexico. It was an Anglo settlement. Almost every type of occupation needed for existence on the frontier was present, and most men listed multiple occupations. There was a physician but no ministers, as the latter were prohibited by law unless they were Roman Catholic. Although every colonist was required to declare that he was loyal to the Roman Catholic faith, almost none were. Many of the inhabitants listed in the census and their descendants had important roles in the events of Texas independence and the later history of Texas. One such descendant was Texas Governor Price Daniel, and others include every member of the Munsons and Caldwells of Texas.

The original census document itself has had an interesting history. Originally it was sent to Stephen F. Austin, and he no doubt forwarded it to Mexican officials. At this point its whereabouts is lost in history for almost a century, at which time, in April, 1921, it appeared for sale by Bernard Quaritch, Ltd., in London, England. The Manuscripts Division of the U. S. Library of Congress purchased nine items from Quaritch for 290 pounds and 14 shillings (about $1,162). Among these was the original Atascosita Census of 1826. The document is now in the Library of Congress, where it may be observed and used.

The results of a vote on September 10, 1826, showed that a majority of the residents desired to be added to Austin's Colony. The results of the vote were sent to "Col. Stephen F. Austin, St. Felipe de Austin", signed by Joseph W. Brown, Duncan St. Clair, George Orr, Alcalde, and Henry W. Munson, Alcalde, and a petition to this effect was forwarded to the political chief in San Antonio. At this time Austin was busy establishing the boundaries of his colony. This task was completed on March 7, 1827, with the eastern boundary being the west bank of the San Jacinto River, less than twenty miles from the Munson homesteads. Orr and Munson believed all to be in order by September 28, 1826, when they wrote to Austin [5]:

. . .As we are now to be under your wing we hope you will find it convenient to call on us with the commissioner and put us quickly in a way to know where our lands are —- we shall be grievously disappointed if the Commissioner does not visit us and set us to rights.

Munson followed with a letter on November 15, 1826, in which he defined the limits of the District as agreed upon by the inhabitants. Munson wrote to Austin:

The Atascosito District is bounded as follows viz. On the West by the Colony of San Felipe de Austin on the north by the District of Nacogdoches, on the east by the reserved lands on the Sabine, on the south by the Gulf of Mexico including all Islands and Bays within three leagues of Sea Shore.

To Col. Stephen F. Austin

Sir Above is stated the limits of the Atascosito District as it was agreed on at the meeting of the inhabitants here and as we suppose ought now to stand. . . if there be any error or defect in defining the limits you will alter or supply it in the translation —— Atascosito District Nov. 15th 1826Henry W. Munson

The petition was finally approved in August of 1828, the same month in which Henry William contracted to move to a plot in Austin's Colony. George Orr expressed the gratitude of the settlers in a letter to Austin dated February 18, 1829. The letter from Orr, who was clearly less educated than Munson, reads as follows:

. . .Grate Satisfaction to hear the Good Tidings that thrue your feling and kind Gratitud that you have perservered in obtaining a Grant for the Lands in this Sacsion of Contra from the honarable Government and I think the Settlers on this River Should never For Get you as their faithful friend.

The district was never joined to the Austin Colony, but in 1830

the Mexican government finally took steps to issue land titles to

the colonists, and the Elizabeth Munson Survey of 4,428 acres was

approved in January of 1831.

The Fredonian Rebellion [6]

Henry William Munson was a participant in suppressing the Fredonian Rebellion in January of 1827. This conflict grew out of an unsuccessful colonization effort in a large area of East Texas centered at Nacogdoches. The disputes appear, at times, to have reached to the Munson lands on the Trinity.

After Mexico gained its independence from Spain in 1821, it established its northeasternmost state as the Province of Tejas, with the capital at San Antonio de Bexar. The first governor was Felix Trespalacios, the uncle of the Spanish officer Mordella. By an act of the Federal Congress on May 7, 1824, the previously separate Provinces of Tejas and Coahuila were united into one state, the State of Coahuila y Tejas, with the capital in Saltillo. This was to cause hardships for the new settlers of Texas. The first Mexican federal colonization plan was published on October 4, 1824, and the State of Coahuila y Tejas adopted the plan on March 24, 1825. All of the empresario grants in Texas except the first of Stephen F. Austin's, a total of twenty-five, were made under this law. Of these twenty-five grants, most came to naught, the exceptions being those of Green DeWitt, Robert Leftwich (known as Robertson's colony), and Martin De Leon.

The Fredonian Rebellion resulted from problems arising out of one of these grants. The Edwards brothers, Haden and Benjamin, had been respected residents of Kentucky and Mississippi, where they were wealthy planters. An empresario contract to introduce settlers to East Texas for an empresario fee was granted to Haden Edwards on April 15, 1825. The area of his grant included most of the land in East Texas to the east of the Austin Colony. It extended to within ten leagues (thirty miles) of the sea and to within twenty leagues of the Sabine River. This apparently included the Trinity settlement at Atascosita where the Munson families had settled just one year earlier. Under his grant Edwards agreed to introduce eight hundred families and act as commander of the militia, but also to respect and protect all who owned land with proper titles. Here an explosive problem was created. Many Spanish families had lived here for decades, but without land titles; while new American settlers had come expecting to claim 4,428 acres of free land under Mexico's colonization law, but no titles had been issued. Now the Edwards brothers claimed that this land would have to be purchased from the empresario, or the settlers would be expelled and the land sold to others.

The Edwards grant included the old settlement of Nacogdoches, first settled in 1716 and thereafter followed by many periods of turmoil. The area contained Spanish residents of all stripes; many claiming land ownership, some with titles but most probably without documentation. In addition, the grant included territory north of Nacogdoches in which the Cherokees and other Indians recently expelled from the United States had been settling. Indian representatives, too, had gone to Mexico City in 1822 to petition for land titles, but being unsuccessful (due to a misunderstanding, according to history), their land had been granted to Edwards.

Finally receiving the grant after three difficult years in Mexico City, Haden Edwards returned to the United States, made extensive arrangements for introducing families, and then moved with his family to Nacogdoches in September of 1825. Learning that many older Spanish claims were being asserted, he twice posted stern notices to all such claimants to exhibit their titles in order that the true might be respected and the false rejected. Since good titles were scarce, this step aroused fear and opposition among natives and settlers alike.

Edwards found the entire local government to be unofficial, so he ordered an election to be held on December 15, 1825. The Alcalde candidates were Samuel Norris, who had the support of the local Mexicans, and Chichester Chapin, who was Haden Edward's son-in-law. An influential local rancher, Jose Antonio Sepulveda, possibly acting as interim Alcalde, presided. The results of the election were disputed and each candidate claimed to have been elected. In March of 1826 the Political Chief in San Antonio de Bexar, Jose Antonio Saucedo, ruled in favor of Norris and declared that, if necessary, the militia would be used to put him in office. He was then allowed to take office peacefully, and Norris and Sepulveda, now in control, became the local officials.

The Edwards brothers set an empresario fee of $520 per league and began to put their plan into effect, evicting at least one claimant and selling his land to a newcomer. Both Edwards brothers had numerous visits and regular correspondence with Stephen F. Austin. At the start this dialogue was friendly and cooperative, but as troubles mounted Austin sided with the settlers and the government. He reported to Haden Edwards that the settlers on the San Jacinto (neighbors to the Trinity settlers) were greatly inflamed by threats attributed to Edwards that he would drive them from their lands unless they paid him his price. On March 10, 1826, Austin wrote to George Orr on the Trinity, apparently in response to such fears, advising caution. A letter dated March 4, 1826, from Haden Edwards to George Orr at Atascosita contained a receipt for $120 paid to Edwards, possibly an initial payment on Orr's land [7]. Austin wrote to Haden Edwards in March of 1826 as follows:

I will here, with perfect candor and in friendship remark that your observations generally are in the highest degree imprudent and improper. . .

The truth is, you do not understand the nature of the authority with which you are vested by the government, and it is my candid opinion that a continuance of the imprudent course you have commenced will totally ruin you, and materially injure all the new settlements.

Most of the year of 1826 saw escalating hostilities between the Edwards brothers and the several other factions. While Haden Edwards was on a visit to the United States, his brother, Benjamin, wrote to Governor Victor Blanco in San Antonio concluding with a denunciation of the local authorities (Norris and Sepulveda) in which he characterized them as corrupt, treacherous, and utterly unworthy. On October 2, 1826, Governor Blanco answered Benjamin Edward's letter, reciting the facts as he claimed to have gained them and concluding as follows:

In view of such proceedings, by which the conduct of Haden Edwards is well attested, I have decreed the annulment of his contract and his expulsion from the territory of the Republic. . .He has lost the confidence of the government, which is suspicious of his fidelity; besides it is not prudent to admit those who begin by dictating laws as sovereigns. If to you or your constituents, these measures are unwelcome and prejudicial, you can apply to the Supreme Government; but you will first evacuate the country, both yourself and Haden Edwards; for which purpose I this day repeat my orders to that department. . .Victor Blanco

On November 22, 1826, a local militia of thirty-six armed settlers led by Martin Parmer entered Nacogdoches. They arrested Norris, Sepulveda, and Haden Edwards, charging them with high crimes, placed them in jail, and named Joseph Durst to the position of Alcalde until an election could be held. A court of five men was named to try the offenders. Norris was impeached with a long list of crimes including corruption, oppression, extortion, treachery, and murderous intent. Sepulveda was found guilty of forgery, treachery, inciting to theft, and swindling. No charges were brought against Edwards and he was released. Norris and Sepulveda were also released under orders to never hold public office again.

By December 15, 1826, the Edwards' group had determined to defend their position by arms and to overthrow the local Mexican government and establish a new nation. Steps were taken to organize armed forces, and a pact of support was made with the nearby Cherokee Indian leaders, John Dunn Hunter and Richard Fields. The Americans assumed the designation of Fredonians, and on December 16, 1826, Benjamin Edwards rode into Nacogdoches under a red and white flag inscribed "Independence, Liberty, and Justice". The object was a declaration of independence from Mexico and the establishment of the Republic of Fredonia. A line was designated north of Nacogdoches with all land to the north to belong to the Indians and to the south to the Americans. A war was to be fought until the achievement of independence. The effort was primarily that of the Edwards brothers and a few supporters — their forces never reached over one or two hundred, and support was tepid. Many settlers returned to Louisiana, not wanting a showdown with the Mexican government.

By January l, 1827, Austin had written to neighboring districts concerning the dangers in Nacogdoches. On January 7 George Orr wrote to Austin asking for information and instructions. The Atascosita District residents chose to take early action — they lived within the disputed district and probably felt more threatened. At the suggestion of Austin, they formed a militia of thirty-one men on January 16. Henry W. Munson is listed as a lieutenant, second in command, on the Muster Roll of Captain Hugh B. Johnston's Atascosita Company. The names of George Orr and Micajah Munson are not on the roll. The volunteers served from January 16 to February 17, l827 [8].

About December 11, 1826, between one and two hundred Mexican troops had left San Antonio for Nacogdoches, traveling by way of San Felipe de Austin where they arrived on January 3, 1827. There their leaders consulted with Austin while they were delayed for three weeks due to heavy rains. A delegation from the Austin and DeWitt colonies was sent to negotiate with the Fredonians. Their mission failed. Archie P. McDonald writes of Austin: ". . .loyal to the government and intolerant of anything which jeopardized his own arrangement with it, he had tried to counsel Benjamin Edwards against such rash acts. . ." [9]

On January 22, 1827, Austin issued the following stern notice:

To the Inhabitants of the Colony:

The persons who were sent. . .from this colony. . .to offer peace to the madmen of Nacogdoches, have returned —— returned without having affected anything. The olive branch of peace which was held out to them has been insultingly returned, and that party have denounced massacre and desolation to this colony. They are trying to excite all the northern Indians to murder and plunder, and it appears as though they have no other object than to ruin and plunder this country. They openly threaten us with massacre and the plunder of our property.

To arms, then, my friends and fellow-citizens, and hasten to the standard of our country!

The first hundred men will march on the 26th. Necessary orders for mustering and other purposes will be issued to commanding officers.

Union and Mexico.

S. F. Austin

The Mexican army left San Felipe de Austin for Nacogdoches on January 22, and Austin's militia followed a few days behind. The Atascosita Company proceeded up the Trinity River by orders from Austin. The total force converging on Nacogdoches numbered about 150 men.

Colonel Peter Ellis Bean, Mexico's Indian Agent for Texas, preceded the army for the purpose of consulting with those Indian leaders who were not in agreement with Hunter and Fields, and who were more sympathetic to the Mexicans. On January 25 he met with these Indian leaders at the Trinity River crossing and gained their allegiance. They were joined on January 26 by the company from Atascosita. Bean then led these men, about seventy in all (and presumably including Henry William Munson) toward Nacogdoches. Finding no Fredonians remaining there, they pursued the rebels, unsuccessfully, to the Sabine.

When the Fredonians had become aware of the approaching armies, they sent runners to the Cherokees to call for assistance. The Cherokees, split between leaders and caught between the promises of the two sides, had switched allegiance, and Hunter and Fields had been murdered. Realizing the hopelessness of their position, the few remaining Fredonians had abandoned Nacogdoches on about January 28, 1827, and retired across the Sabine to Louisiana.

Historians report that a number of prominent colonists were present when the main Mexican army occupied Nacogdoches, and that they aided in the protection of all who remained in the town. It is presumed that Stephen F. Austin and Henry William Munson were among these men. Austin's militia was immediately discharged to save expenses, but the Atascosita men may have remained for some days, as they were not discharged until February 17. Norris was reinstalled as Alcalde, and Austin himself remained in Nacogdoches for more that a month to help restore order. This may have been the occasion when Austin and Munson became personally acquainted and discussed Munson's future move to the Austin Colony.

When Henry William Munson returned home and left the militia on February 17, 1827, his wife was again pregnant. Sometime in the year 1827 she gave birth to the only daughter that they were to have among their eight children. They named her Amanda Caroline Munson. Similar to the other such tragedies which befell their babies, this daughter was to survive for only about one year.

In November of 1827, Henry William Munson was one of the signers of a petition to Don Bustamante, Commander General of Internal States (of Mexico), again asking to be part of Austin's Colony as the settlers in the Atascosita District could not obtain title to their lands. The experiences in the Fredonian fiasco had probably emphasized the need for good titles, and failure of action here must have been the last straw. Family tradition tells that Henry and Micajah both planned to move their families to Austin's Colony, but that Micajah died (possibly before the Fredonian Rebellion), and his wife, Elizabeth, decided to remain behind with her two daughters.

On August 27, 1828, at the plantation home of future neighbor,

John McNeel, Henry William Munson signed an agreement ![]() with Stephen F. Austin to

buy land on Gulf Prairie in the Austin Colony and to move there

within four months.

with Stephen F. Austin to

buy land on Gulf Prairie in the Austin Colony and to move there

within four months. ![]() This land was in Austin's

fourth and last empresario contract (dated on maps as May

31, 1828, but finally approved on July 17, 1828). For the first

time, it allowed empresario settlements within ten leagues

of the coast.

This land was in Austin's

fourth and last empresario contract (dated on maps as May

31, 1828, but finally approved on July 17, 1828). For the first

time, it allowed empresario settlements within ten leagues

of the coast.

There followed in November of 1828 the barge trip taken by Henry

William, Ann, William Benjamin, Mordello Stephen, Amanda Caroline,

and twenty slaves down the Trinity, across Galveston Bay and the

Gulf to the Brazos River, and up the Brazos to the area of Jones

Creek. Amanda Caroline died en route and was buried at sea. And

thus the Munsons of Texas arrived at their home in the future

Brazoria County.

____________________

- [1] The material for this section is taken mostly from John Henry Brown, History of Texas; and Eugene C. Barker, The Life of Stephen F. Austin.

- [2] Volume D, page 340, Deed records, Liberty County, Texas.

- [3] Miriam Partlow, Liberty, Liberty County, and the Atascosito District, The Pemberton Press, Austin, 1974, p. 302.

- [4] The original document is in the Library of Congress, Washington, D. C. A reprint was published for the Liberty County Historical Survey Committee (Liberty County Historical Museum) from Vol. 1, No. 4 (Fall, 1963), Texana (Magazine).

- [5] This and following letters are from Eugene C. Barker, The Austin Papers, Barker Texas History Center, University of Texas, Austin; and the Munson Papers, see Appendix 1.

- [6] The material for this section is taken from Eugene C. Barker, The Life of Stephen F. Austin; Edmund Morris Parsons, "The Fredonian Rebellion", Texana (Magazine), Spring, 1967; Archie P. McDonald, Nacogdoches, Wilderness Outpost to Modern City, 1779-1979, Barker Texas History Center, University of Texas, Austin; and John Henry Brown, The History of Texas.

- [7] This and the following letter are from Eugene C. Barker, The Life of Stephen F. Austin, pp. 155-157.

- [8] Miriam Partlow, Liberty, Liberty County, and the Atascosito District, p. 72-76.

- [9] Archie P. McDonald, Nacogdoches, Wilderness Outpost to Modern City.